How a girl born at 2 pounds became a happy boy

Related Links

The night before his surgery, Rancho Bernardo’s Sam Moehlig woke up several times.“Then I’d see it’s 2 in the morning and go back to bed.”

He rose again at 4:30 for an early breakfast, his last meal before his 2 p.m. operation in a Thousand Oaks clinic. Going under the knife, the 14-year-old said later, “was kind of like a dream.”

“It was just pure excitement, just pure anticipation,” he said. “I was finally getting rid of something that had been bothering me for years.”

Sam, who was born female, got rid of his breasts.

A boy’s new life

Gender reassignment operations are controversial, especially for minors. Dr. Paul McHugh, the University Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, opposes them outright. Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego will not recommend surgery for anyone younger than 16.

That’s “due to the irreversibility of the procedure,” said Dr. Maja Marinkovic, medical director of Rady’s gender management clinic. “Adolescents may not have the capacity to make informed decisions.”

Sam’s surgery came after years of anguish and depression. His suicidal thoughts eased when a psychiatrist suggested that Sam might be experiencing “gender dysphoria,” the intense sense that someone’s body and sexual identity are in conflict.

More counseling followed, as well as hormone blockers, testosterone shots and constant talks with his parents, Kathie and Ron, and his sister, Jacq. Sam’s struggle has been a team effort.

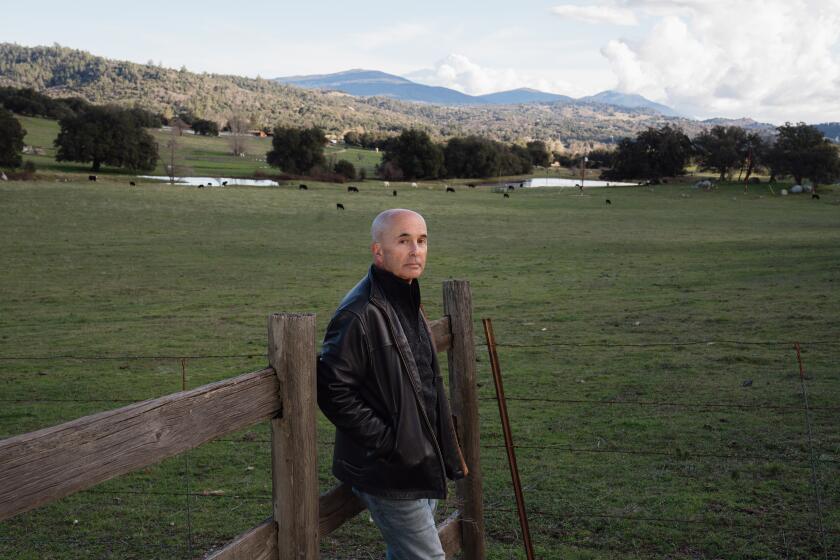

Sam’s double mastectomy was “the next step in our family as our family grows and gets closer,” said Ron, 62, a service adviser for a local automobile dealership. “God has plans for everybody, and this is how it develops.”

![]()

‘Boy birthday’

Recovering alcoholics, Ron and Kathie met 27 years ago in a 12-step meeting. Once he gained sobriety, Ron had assumed that his days would follow a predictable middle-class trajectory. Instead, life took an unforeseen turn.

“That’s not what you expect,” he said of his child’s passage from female to male, and the ripples this sent through the family. “But it seems like the new normal for us now. Sam’s here for a reason.”

Sam was born on Oct. 20, 2000, at Sharp Memorial Hospital. The Moehligs adopted Samantha from her homeless birth parents, tending the baby through fetal alcohol syndrome. Breathing was such a trial, her skin would turn blue. The infant needed nine medications and, from the age of six months until 3, feeding tubes.

Despite this fragile start, Samantha grew up to become a boisterous kid who loved sports and sci-fi movies. While she thought of herself as a boy, her body had other ideas. Her breasts began developing around the age of 9, plunging her into what Kathie calls “the deep dark.”

Clinically depressed, Samantha spoke of suicide. Frantic, her parents sought counseling for their child and searched everywhere for clues. All along, Kathie now believes, she was hunting for a word.

“I feel the guilt of knowing that your child is suffering for years,” said Kathie, now 54, “and then finding the term: transgender.”

Counselors and physicians agreed: This was a case of gender dysphoria. On April 6, 2012, Samantha adopted a male persona and name.

Ever since, that has been Sam’s “boy birthday.”

His body, though, did not cooperate. At tae kwon do, he wore a white T-shirt under his uniform to keep breasts from slipping out. After surfing lessons, he wrapped his torso in a towel while pulling off his wetsuit.

A hormone blocker was implanted in his left bicep to slow the growth of female characteristics. He bound his torso to minimize telltale curves. Two years ago, testosterone shots were added to his routine. To all outward appearances, he became a typical boy.

Related Links

Within a certain community, though, Sam’s posture was a giveaway.

“I don’t know any trans guys who don’t have their shoulders pulled forward,” said Aydin Olson-Kennedy, 39, a transgender man who became Sam’s counselor in 2014. “It’s hard to undo and unpack the discomfort that gender dysphoria causes. It is deep and it is very, very profound.”

![]()

See you in Heaven?

Sam began his “social” transition, living as a boy. This wasn’t a dramatic change — at least since kindergarten, he had identified himself as a boy. From his first “boy birthday,” though, Sam became “he” in everyone’s eyes.

Almost everyone’s. So far, one set of grandparents has refused to accept their grandchild as a boy — or, as the rest of the family sees it, accept Sam as Sam.

This rift continues, yet Sam holds out hope that eventually these relatives will support him. After all, Sam has a large support group. All of his uncles and aunts know about his journey and support their nephew.

Jacq made her feelings clear at last summer’s Pride Parade in Hillcrest. The 21-year-old held a sign: “My Brother Was My Sister. So What?”

As Sam changed, so did his family. “Parenting evolves,” Kathie said, “and I’ve evolved as a part of this experience.”

Last June, she incorporated a nonprofit for families with transgender youth. Since October, her TransFamily Support Services has worked with 36 clients in a half dozen states and one Canadian province. She’s successfully advised seven families on how to have top surgery covered by insurance.

Ron marched with Sam in last year’s Pride Parade. “I can’t wait to march with him this year,” he said.

“Sam has parents who were on his side and advocating for him,” said Sam’s counselor, Olson-Kennedy. “I have clients whose parents are super not — and the idea of losing your family is just too painful.”

Home-schooled, Sam didn’t face snarky comments from classmates. No administrators barred him from the boys’ locker room. Awkward moments have been rare, although there was one at the Presbyterian church the family had attended for 10 years.

Watching Sam, several worshippers who had been friendly with the Moehligs expressed misgivings.

“When you and Ron die,” one told Kathie, “you won’t be with us in heaven.”

The Moehligs left that church and eventually found a spiritual home at Agape International. One Sunday a month, they drive to Culver City to attend services with this non-denominational congregation.

As a youngster, Sam sometimes wondered: Had the Almighty goofed? Why would an all-wise, all-loving deity saddle a child with the wrong gender?

He no longer wonders.

“I am grateful I was born the way I was,” he said. “I look back on it and I don’t think I would be the type of person I would be” without this experience.

“You can develop into who God intended you to be.”

![]()

64 likes

On the morning of July 23, the entire family piled into a van and drove north, bound for the Kryger Institute for Plastic Surgery in Thousand Oaks. The trip was interrupted several times for meals — for Jacq, Ron and Kathie.

There were bagels at an Einstein Bros. in Oceanside, then burgers at the Red Robin in Thousand Oaks.

While everyone else noshed, Sam sipped water and leaned against his mother.

“I think this is worth not eating,” Jacq said.

“Yeah,” Sam said. “I know.”

At the clinic, Sam was taken to a private room for photos of his chest. Then he returned to the waiting room for a family portrait. Finally, he was escorted into the operating room.

Related Links

“Love you!” Jacq yelled at the departing figure.

“Love you!” Ron called out.

“See you soon!” Kathie said.

From her cellphone, Jacq uploaded a shot of Sam to Facebook. By the time the surgery was completed, her post had 64 likes and 35 comments.

![]()

‘Natural state’

For the last four years, Drs. Gil and Zol Kryger have averaged 100 “top surgeries” a year, each costing $6,000 to $9,000. “Bottom surgery,” constructing genitalia, is comparatively rare and far more expensive, running $75,000 to $100,000.

Sam is unsure he’ll ever have bottom surgery. “You can get away with not having a part,” Kathie said. “You can’t get away with having parts that don’t belong. This, the top surgery, is a necessity.”

Still, is someone Sam’s age too young to alter something as personal and intimate as gender?

“They’ve all known their entire life, from their earliest memory” that their bodies did not reflect their true gender, said Zol Kryger, 44. “It’s just like you and I. We know. That’s hardwired into our brain.”

While the Kryger brothers are plastic surgeons, they reject the notion that these are “cosmetic” operations.

“This,” Zol Kryger said, “is surgery to restore someone to their natural state.”

After two hours in the O.R., a still-sedated Sam was returned to his family.

“Everything,” Gil Kryger told the Moehligs, “went exactly as planned.”

The family drove to a nearby motel and tucked Sam into bed. Overcome by events, Ron shed a few tears. He was relieved the family would no longer have to battle insurance companies, pressing them to cover the operation.

“There was a lot of stress, not just for Sam but for the family,” Ron said. “We wondered: Will it get approved?”

It was, and the surgery had been successful. “For him,” Ron said. “His own comfort. The way he’ll be accepted. Not having to hide anything. The barriers are down. He can do whatever he wants to do, be whatever he wants to be and do it from his authentic self.”

![]()

Catch a wave

The day after his surgery, Sam woke up famished and elated. “It was everything I ever wanted,” he said.

Yet the immediate aftermath was a trial. Sam had to miss team practices and competitions as his body healed. His parents waited until Aug. 29, a month after the surgery, before throwing a pool party for the boy and his friends.

Sam was thrilled: “I felt like that was my entire lifetime of wanting to take my shirt off at the pool.”

Two weeks later, he resumed surfing lessons with one of his home-school teachers, Johnny Pontecorvo. At the beach outside Oceanside Harbor, Sam paddled a 9-foot Styrofoam board into the 4-foot swells.

He wiped out a few times and chased several waves in vain. Maybe 20 minutes into the session, Sam paddled down the face of a wave, rose to his knees, then popped onto his feet.

“I paddled and caught it!” he told his parents, minutes later on the sand. “Caught it!”

“He’s excited to get back to his usual things,” Ron said.

That was a Sunday. The following Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, he would resume gymnastics practice; Friday, flag football; Saturday, tae kwon do.

“Guess what?” he asked Pontecorvo. “I finally get to be a boy!”

![]()

DARTHSAMWISE

In 2015, Sam’s calendar held two red letter dates: July 23, the date of his surgery, and Dec. 17, when “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” debuted in late-night screenings.

The original “Star Wars” opened in 1977, when Jimmy Carter occupied the White House, Leonid Brezhnev ran the Soviet Union and Elvis left the building once and for all. Sam has no memories of those last three historic figures, but he’s memorized the movie.

Related Links

“I saw it as soon as I was born,” he said, piloting a TIE fighter over the ice planet Hoth, “and thought it was totally awesome.”

He was at a friend’s house in Rancho Peñasquitos, immersed in “Star Wars — Battlefront.” After seven hours of this video game, Sam and two friends would line up outside the Edwards Mira Mesa Stadium 18 for “Force,” the latest movie in the “Star Wars” series.

Sam was dressed for the occasion: A gray T-shirt with Darth Vaderesque logo, “I FIND YOUR LACK OF STRENGTH DISTURBING,” and black pants with STAR WARS stamped on the seam and an Imperial Stormtrooper’s white mask emblazoned on one leg.

On two flat-screen TVs, adventures unfolded on the frozen wastes of Hoth, the forests of Endor, the interstellar reaches of a fantastic galaxy. Beneath each player’s avatar, including those of distant people playing the game online, was a call sign.

DARTHSAMWISE was killed by WillTheThrill714, MEDICxx30 and ASIANinvasion-21. He was blown apart in a TIE fighter crash.

“It takes a little while to get used to flying,” said Sam’s host, Tim Wazny.

Wazny is 24. While singing in the church choir with Jacq, he met Sam. He’s equally passionate about sports, “Game of Thrones,” and Frank Herbert’s science fiction novels about the planet Dune. Wazny has become a role model to the younger guy.

An evangelical Christian who plans to become a minister, Wazny is not bothered by Sam’s transition.

“I can’t remember when I didn’t know Sam,” Wazny said. “He’s become a very good friend.”

![]()

Dec. 25

Few people have commented on Sam’s new, flatter physique. The silence can bother the teen, and once he tried to provoke a conversation.

“Oh,” he said, “I had my breasts removed.”

His friends’ response: “OK.”

“That creeped me out a bit,” Sam said later. “Where are the questions? Why aren’t they asking? I’d expect: ‘How did it happen?’ Or: ‘Why?’ I’m ready here. But they just say ‘OK.’ It makes me a little nervous.

“I think maybe they don’t know how to ask without offending me.”

If friends had seen Sam on Christmas morning, they would have understood the power of this change. Opening presents was fun, but the highlight of Sam’s day came when he retreated to the bathroom.

“The best Christmas present I ever got,” he said. “The gift of a Christmas shave!”

Toting a twin-blade razor and a tube of shave butter, Sam prepared for his first shave. Ron was at his side, coaching the boy, while Kathie took photos and Jacq watched.

This was a family occasion — “a little weird, everyone jammed in there,” Sam said — yet it was especially significant for the guys.

“The whole relationship of father and son rather than father and daughter has changed,” he said. “We are able to relate a little closer.”

Ron helped oversee this traditional rite of passage from boyhood to manhood. Apparently, the old man did a good job.

“I didn’t cut myself,” Sam said. “That was a step in the right direction.”

![]()

Testimony

A happy winter gave way to an eventful spring. An avid reader and creative writer, Sam worked hard in school. Flag football was a blast — “I was not worrying about my breasts bouncing all over the place” —and his balance in gymnastics improved.

“Gravity,” he noted, “has the advantage. Surgery made it 10 times easier than before.”

His “boy birthday” was Wednesday, and in the weeks leading up to this landmark day, he looked forward to teasing his sister. Jacq had to wait for her 18th birthday to get her nose pierced. She was unaware that their parents had OK’d Sam getting an ear pierced at 151/2.

Related Links

“I’m going to walk into her room and tell her, ‘Jacq, my ear really hurts,’” Sam said. “My sister is going to freak out.”

Even without bling, people see changes in Sam. He stands straighter, speaks more confidently, smiles more easily.

“When I first met him, Sam was so shy,” said Olson-Kennedy, who began counseling Sam almost two years ago. “Now, he is just so much more available.”

Available, even a bit outspoken. Kathie and Sam’s plans for last week included a trip to Sacramento, to lobby on behalf of LGBT youth. Once depressed and withdrawn, Sam was eager to testify.

“People need to hear it,” he said. “For some of the youth and even adults who don’t want to speak out and be heard, it’s good that people are.

“Every person is different. That’s who I am.”

![]()

Awareness rising of transgender youth

Netflix’s “Orange is the New Black.” Amazon’s “Transparent.” TLC’s “I Am Jazz.” E!’s “I Am Cait,” a reality show following the former Olympian Bruce Jenner in her post-surgery identity, Caitlyn Jenner.

On TV, we’re witnessing a transgender population explosion.

In real life? It’s unclear how many Americans have made this transition. Last May, the U.S. Census Bureau attempted an estimate, drawing on “changes to individuals’ first names and sex coding”: almost 90,000.

“It’s a lot bigger than what anyone ever thought,” said Dr. Johanna Olson, medical director of the Center for Transyouth Health and Development at Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles.

Olson joined the center a decade ago, when there were 40 patients. Now, there are 640. In San Diego, the gender management clinic at Rady Children’s Hospital admitted 60 new patients last year.

“The numbers are dramatically increasing,” said Dr. Maja Marinkovic, Rady clinic’s medical director.

How to treat these patients, though, is a question fraught with ethical and political pitfalls. Last year, Dr. Kenneth Zucker was fired from a Toronto gender identity clinic. His offense? The psychologist was accused of encouraging some young patients to accept the gender they were assigned at birth.

Others, including a group called 4thWaveNow, are openly skeptical of what they call “the ‘transgender child’ trend.”

“This is a clinical issue that is becoming a culture war issue,” said Dr. Jack Drescher, a New York psychiatrist and psychoanalyst.

Drescher helped write the sexual identity guidelines for DSM-5, the diagnostic reference book used by the American Psychiatric Association. He also helped develop standards of care for the World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

Yet even he is not sure when and how children should be treated for gender dysphoria. Each case, he noted, is different.

Think of a girl who dresses as a boy, or a boy who tries on his mother’s dresses. Are these signs of innate, lifelong yearnings, or a passing childhood phase?

“The majority of pre-pubescent children who present as gender dysphoric do not persist,” Drescher said. “There’s desistance, according to the majority of the research literature.”

That literature, though, is far from conclusive. Some studies indicate that we know who we are from an early age.

“It is pretty well proven that people know their gender by the age of 5,” said the Center for Transyouth Health and Development’s Olson. “If we accept and believe that people know their gender by the age of 5, why not accept that trans kids know their authentic gender?”

Treating young people with gender dysphoria is critical, Olson said, as puberty increases the chances they will harm themselves.

“One of the things that puts trans kids at higher risk is this period of time when they are going through puberty,” she said. “Their body is becoming the adult or permanent version of this body they are not comfortable with.”

Drescher countered that “we don’t always have enough information to make a decision based on empirical data.”

Still, he said, surgery “could be the right decision for a number of young adolescents.”

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.